Neurons that regulate a mouse’s response to hunger and thirst also influence social interactions with the opposite sex.

Under the right circumstances, even moderately hungry mice prefer to socialize with the opposite sex than to eat, researchers have found.

In research published on 23 February in Cell Metabolism, scientists treated male mice with a technique that mimics the effects of leptin, a hormone that acts on the brain to suppress appetite. Treated mice were more likely to approach female mice than their food bowls — even if the test rodents had been deprived of food for almost an entire day.

The findings reveal a surprising role for leptin in social behaviour. They are also a step towards understanding how animals prioritize different behavioural options in response to ongoing needs — an enduring question in neuroscience, says Gina Leinninger, who studies the neural regulation of feeding at Michigan State University in East Lansing. The paper “addresses a huge gap in the field”, she says. “When you no longer need to eat urgently, it should free you up to do other things.” The new work, Leinninger says, illuminates how the brain juggles these various demands.

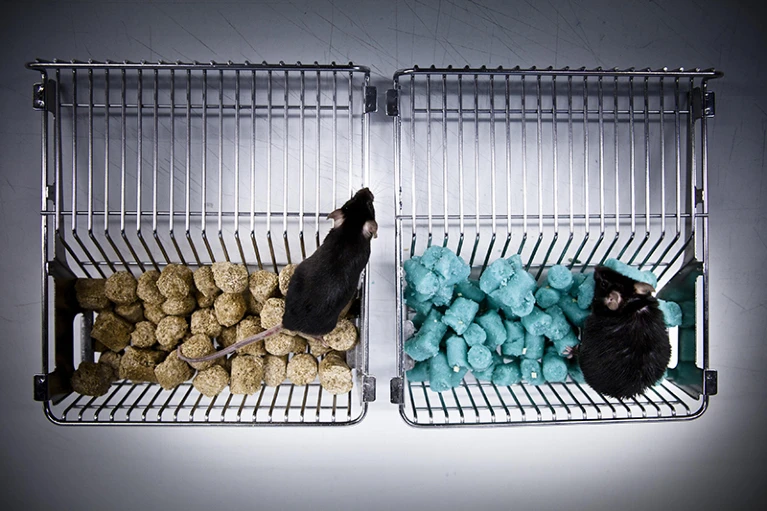

Food versus friends

Neuroscientists Anne Petzold and Tatiana Korotkova at the University of Cologne in Germany, and their colleagues, sought to understand how such decision-making is affected by leptin, which activates a subset of cells in the brain and promotes a feeling of fullness. The researchers injected male mice with leptin and saw that it suppressed feeding, as expected — but also promoted interactions with female mice.

The team examined neurons in the brain’s ‘hunger center’, the lateral hypothalamus, that are activated by leptin. The authors’ experiments showed that neurons that can sense leptin were activated when mice interacted with members of the opposite sex. Artificially activating those neurons using a technique called optogenetics raised the likelihood that a mouse would approach a member of the opposite sex. Both results suggest that leptin plays a part in promoting social behaviour.

Surprisingly, even mice that had limited access to food for a day were more likely to bypass their mouse chow and seek out members of the opposite sex when their leptin-activated neurons were stimulated with optogenetics. But in mice that had been given limited access to food for five days, hunger won out over socializing. “Following prolonged hunger, other systems kick in and make food a higher priority,” says Korotkova.

The team also studied neurons that produce a hormone called neurotensin that is related to thirst. Stimulating these neurons promoted drinking over eating or social behaviour.

Hierarchy of needs

Researchers have typically thought of leptin as being important for responses to metabolic signals rather than social cues, says Scott Sternson, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego. “But now that we see these results, it makes sense,” he says. Leptin is normally produced when an animal’s energy needs have been met, and that feeling of satiety could allow the animal to refocus its attention away from food and towards other interests. “And it appears that one of these is interest in the opposite sex.”

The study is unique in its complexity, monitoring two classes of neuron under a variety of conditions. But there are dozens of other cell types in the lateral hypothalamus, Sternson notes, and these might also have important roles. He and his colleagues have tracked the activity of 10 brain-cell types across 11 behaviours, but the experiment was so complicated that it limited the number of animals that the team could study, and the animals were not free to move around as they pleased, he says.

Although it is impossible to extrapolate directly from mouse to human behaviour, the leptin system is conserved in a wide range of animals. “Even flies express leptin receptors,” Petzold says.

This means that studying the interaction between leptin and social behaviours in mice could hold clues to understanding the disordered eating exhibited by some people with autism, for example, or the social phobia seen in some people with bulimia, says Korotkova.

“There is a myriad of diseases that are desperately affecting humans that are all about this: do we need to eat more or drink more or not,” says Leinninger. “Figuring out how to tweak that circuitry could be hugely impactful for health.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00521-3

References

-

Petzold, A., van den Munkhof, H. E., Figge-Schlensok, R. & Korotkova, T. Cell Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.008 (2023).

-

Xu, S. et al. Science 370, eabb2494 (2020).