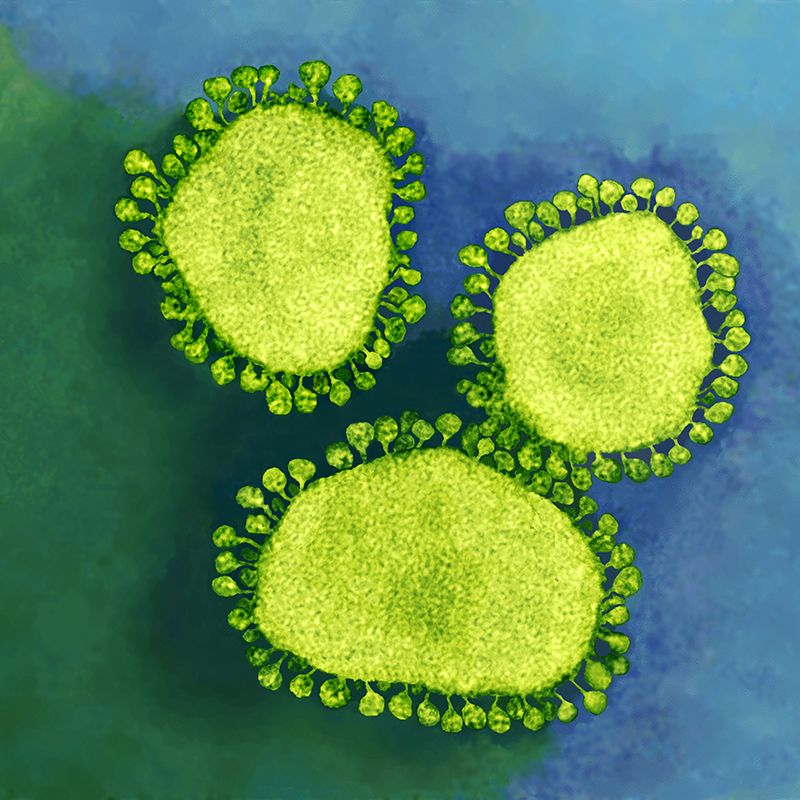

Credit: Dr Linda Stannard/UCT/Science Photo Library

With no sign that an outbreak of a new coronavirus is abating, virologists worldwide are itching to get their hands on physical samples of the virus. They are drawing up plans to test drugs and vaccines, develop animal models of the infection and investigate questions about the biology of the virus such as how it spreads.

“The moment we heard about this outbreak, we started to put our feelers out to get access to these isolates,” says Vincent Munster, a virologist at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Hamilton, Montana. His lab is expecting to receive a sample in the next week from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, which has led the response to US cases of the virus.

The first lab to isolate and study the virus, known provisionally as 2019-nCoV, was at the epicentre of the outbreak: in Wuhan, China. A team at the Wuhan Institute of Virology led by virologist Zheng-Li Shi isolated the virus from a 49-year-old woman, who developed symptoms on 23 December 2019 before becoming critically ill. Shi’s team found1 that the virus can kill cultured human cells and that it enters them through the same molecular receptor as another coronavirus: the one that causes SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome).

A lab in Australia announced on 28 January that it had obtained virus samples from an infected person who had returned from China. The team was preparing to share the samples with other scientists. Labs in France, Germany and Hong Kong are also isolating and preparing to share virus samples they obtained from local patients, says Bart Haagmans, a virologist at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. “Probably next week we will get isolates from one of the different labs,” he says.

Sequences vs samples

The first genome sequence of the virus was made public in early January, and several dozen — taken from various people — are now available. The sequences have already led to diagnostic tests for the virus, as well as efforts to study the pathogen’s spread and evolution. But scientists say that sequences are no substitute for virus samples, which are needed to test drugs and vaccines, and to study the virus in depth. “It is essential that viruses are shared,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, in a 29 January press conference.

Munster says that his lab’s first priority will be to identify animals that experience the infection in a similar way to humans. Such animal models will be useful for testing vaccines and drugs. The team first plans to look at a mouse genetically engineered to contain a human version of the receptor that SARS virus and the new coronavirus uses to infect cells. Future work could involve exposing mice and, later, non-human primates to the virus and testing whether vaccines can prevent infection, he adds.

Munster’s lab is also eager to start gauging how long the virus can survive in the air or in saliva droplets. This could help epidemiologists to understand whether the virus can be transmitted through the air, or only through close contact. Munster’s study will involve aerosolizing virus particles using a container called a Goldberg drum, and then measuring their ability to infect human cells after periods of time in the air.

Such experiments will be conducted under strict containment measures — known as biosafety level 3 — to prevent lab workers from becoming infected and to avoid accidental release of the pathogen. Thousands of such labs exist around the world, but Munster notes that much of the research on the virus can be done under less stringent biosafety conditions, which should speed the research.

Tracking the spread

One of Haagmans’ first priorities will be to develop a blood test for antibodies against the virus. This will allow researchers to identify people who have been exposed to 2019-nCoV, but are no longer infected and may have never developed symptoms.

His team also hopes to see whether another animal can serve as a model for human infections — ferrets. Researchers use the animals to study influenza and other respiratory illnesses because their lung physiology is similar to that of humans, and they are susceptible to some of the same viruses. Haagmans hopes to test whether they can transmit the virus between them, seeking insights into the pathogen’s spread between humans.

Many of the questions virologists plan to ask about 2019-nCoV are based on findings from previous studies on the viruses behind SARS and the related Middle East respiratory syndrome. For instance, there have been signs that a protein needed for the SARS virus to infect cells has adapted to enter human cells more easily.

Although for now Haagmans is scrambling to get his hands on just one virus sample, he hopes to eventually have multiple samples from over the course of the outbreak to see whether and how the virus evolves. “We need to get a better understanding of the biology of the virus, especially compared to viruses that we already know,” he says. “That’s what we’re going to do.”